August 28, 2019

Bandera first place in Texas to use new flood early warning system

By Jessica Goode

The Bandera Prophet

On Monday, the U.S. Geological Survey and the Texas Water Development Board gathered at the Bandera County River Authority and Groundwater District offices to unveil a Medina River flood early warning system.

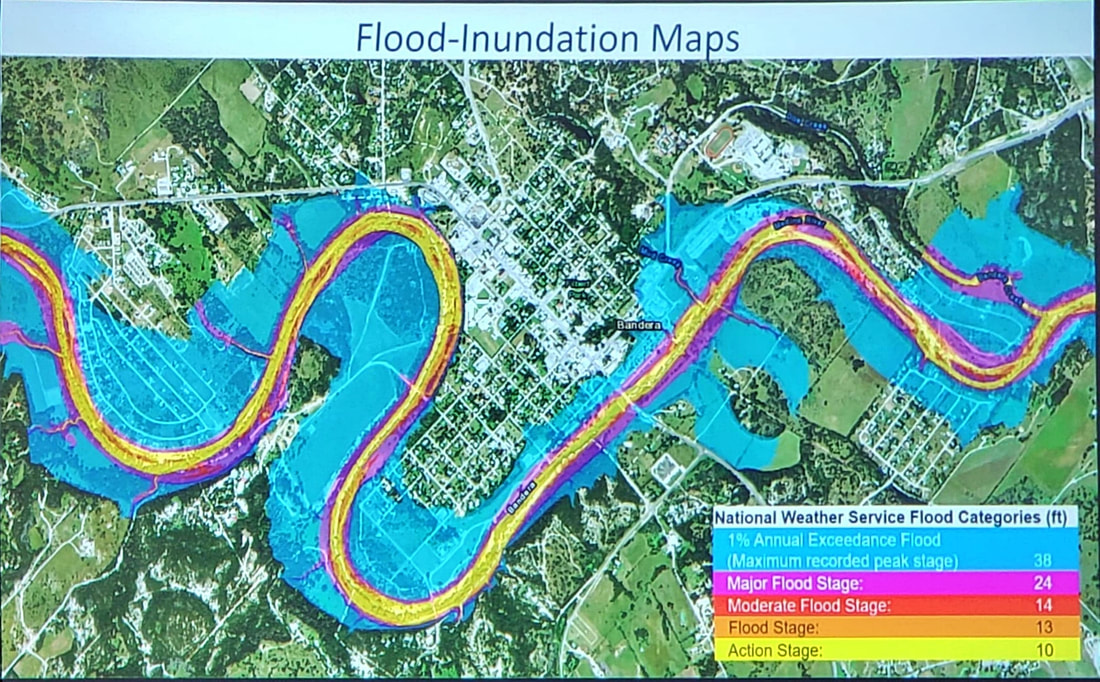

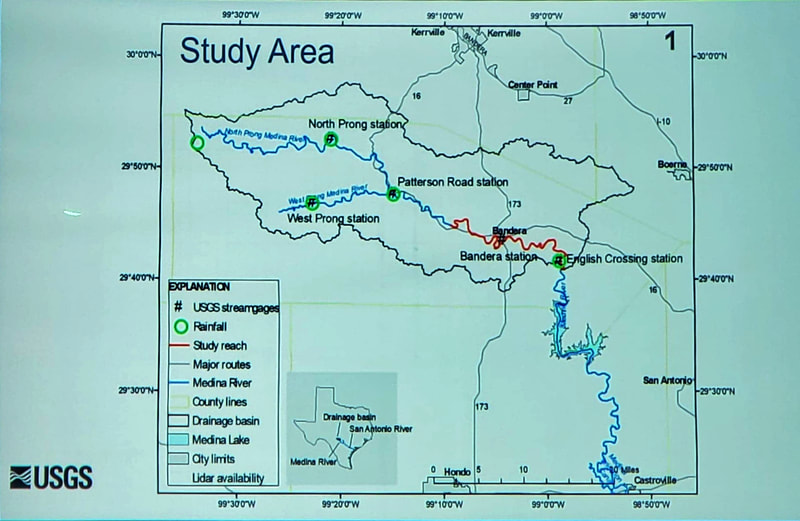

Two new USGS real-time streamflow gaging stations have been installed upstream from Bandera on the west and north sections of the river near Medina, and 29 interactive flood inundation maps have been studied, tested and implemented along the 23-mile stretch of the Medina River. Bandera is the first site in the state of Texas to use the flood inundation mapping program.

“These new flood-preparedness tools will give emergency managers the ability to coordinate a precise response during flood events to help protect lives and property,” BCRAGD General Manager David Mauk said.

The maps illustrate water levels at 10, 13,14, 24 and 38 feet at the Bandera stream gaging station. Emergency responders can use each map to identify areas that may become flooded and begin evacuations.

Bandera County experienced several severe floods in 1978, 2002, 2015 and 2016, and is known as flash flood alley during heavy rain events.

“I’ve been here my whole life. I’ve seen a lot of floods. I’ve seen loss of life,” Bandera County Judge Richard Evans said, recounting when he was an EMT in 1978. “We lost 11 people. Some people we never found.”

Evans said some newcomers to Bandera County have never seen a flood, much less are aware of how quickly and high the waters can rise.

“They don’t know what happens here. They have no idea when it rains 20 inches upstream, we’re going to get a 10-foot wall of water. From the headwaters it takes about eight hours to reach Bandera,” Evans said. “We’re lucky to have a system in place now. This is the beginning of the flood warning system, not the end of it. Institutional memory is going to be gone when we all retire. We have to have a system in place that uses science, not just memory. We have to know as soon as possible so we can begin to evacuate.”

Doug Schnoebelen, chief of the USGS South Texas Program Office in San Antonio, said the project is the building block of a warning system that will go out nationally.

“We’re going to get better to save more lives and more property,” Schnoebelen said. “We’ve had floods in the past, we’re going to have floods in the future. We can’t stop the floods. But we can do a better job of being prepared. This is the beginning of new tools to be able to do that.”

In 1978, 48 inches of rain fell in 72 hours. That storm held the record until Hurricane Harvey. To give perspective, Schnoebelen compared a cubic foot to about the size of a basketball: 46,700 cubic feet per second - the amount recorded - is equivalent to 46,700 basketballs going by every second.

“It’s a tremendous amount of water,” he said.

The gages in place record rainfall in real time - the north prong stream gage records and sends data every 15 minutes. The information collected not only helps responders downstream, but also goes into the model to help with future planning.

“The longterm collection of data is critical,” Schnoebelen said. “The gage in Bandera has been there since 1982. When that gage went in, it may not have been known that it would be used for this model.”

To get the word out, numerous web-based tools are available to emergency planners and the general public.

Each gage is equipped with WaterAlert, a service that provides users with text or email messages when water exceeds a user-defined level. Other USGS flood resources that provide water and weather information include the Texas “Water on the Go” application, the USGS Texas Water Dashboard, Twitter feeds, and @USGS_TexasFlood and @USGS_TexasRain for desktop and mobile devices.

“We don’t need to lose anybody to a flood. That’s not acceptable,” Evans said, adding measures such as sandbagging are futile when facing a surging wall of water. “We just need to get people out of the way.”

Two new USGS real-time streamflow gaging stations have been installed upstream from Bandera on the west and north sections of the river near Medina, and 29 interactive flood inundation maps have been studied, tested and implemented along the 23-mile stretch of the Medina River. Bandera is the first site in the state of Texas to use the flood inundation mapping program.

“These new flood-preparedness tools will give emergency managers the ability to coordinate a precise response during flood events to help protect lives and property,” BCRAGD General Manager David Mauk said.

The maps illustrate water levels at 10, 13,14, 24 and 38 feet at the Bandera stream gaging station. Emergency responders can use each map to identify areas that may become flooded and begin evacuations.

Bandera County experienced several severe floods in 1978, 2002, 2015 and 2016, and is known as flash flood alley during heavy rain events.

“I’ve been here my whole life. I’ve seen a lot of floods. I’ve seen loss of life,” Bandera County Judge Richard Evans said, recounting when he was an EMT in 1978. “We lost 11 people. Some people we never found.”

Evans said some newcomers to Bandera County have never seen a flood, much less are aware of how quickly and high the waters can rise.

“They don’t know what happens here. They have no idea when it rains 20 inches upstream, we’re going to get a 10-foot wall of water. From the headwaters it takes about eight hours to reach Bandera,” Evans said. “We’re lucky to have a system in place now. This is the beginning of the flood warning system, not the end of it. Institutional memory is going to be gone when we all retire. We have to have a system in place that uses science, not just memory. We have to know as soon as possible so we can begin to evacuate.”

Doug Schnoebelen, chief of the USGS South Texas Program Office in San Antonio, said the project is the building block of a warning system that will go out nationally.

“We’re going to get better to save more lives and more property,” Schnoebelen said. “We’ve had floods in the past, we’re going to have floods in the future. We can’t stop the floods. But we can do a better job of being prepared. This is the beginning of new tools to be able to do that.”

In 1978, 48 inches of rain fell in 72 hours. That storm held the record until Hurricane Harvey. To give perspective, Schnoebelen compared a cubic foot to about the size of a basketball: 46,700 cubic feet per second - the amount recorded - is equivalent to 46,700 basketballs going by every second.

“It’s a tremendous amount of water,” he said.

The gages in place record rainfall in real time - the north prong stream gage records and sends data every 15 minutes. The information collected not only helps responders downstream, but also goes into the model to help with future planning.

“The longterm collection of data is critical,” Schnoebelen said. “The gage in Bandera has been there since 1982. When that gage went in, it may not have been known that it would be used for this model.”

To get the word out, numerous web-based tools are available to emergency planners and the general public.

Each gage is equipped with WaterAlert, a service that provides users with text or email messages when water exceeds a user-defined level. Other USGS flood resources that provide water and weather information include the Texas “Water on the Go” application, the USGS Texas Water Dashboard, Twitter feeds, and @USGS_TexasFlood and @USGS_TexasRain for desktop and mobile devices.

“We don’t need to lose anybody to a flood. That’s not acceptable,” Evans said, adding measures such as sandbagging are futile when facing a surging wall of water. “We just need to get people out of the way.”