Photos by Chris Darus & Harvey Raab

September 2, 2019

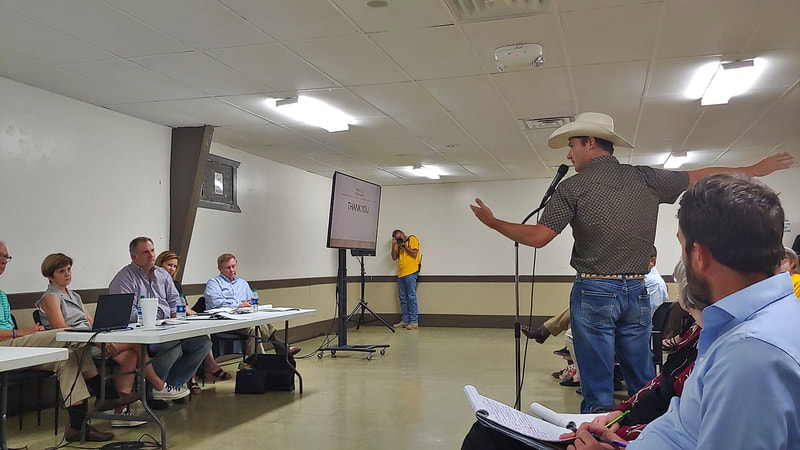

Wastewater discharge permit applicant Sam Torn faces wall of opposition from neighbors who challenge his claims

By Jessica Goode

The Bandera Prophet

An excess of 300 people in opposition of a wastewater discharge permit request attended a Texas Commission on Environmental Quality public hearing last week. The permit request, submitted by Sam Torn, of RR 417, LLC, is for the development of a youth camp near Tarpley. Standing room only was left in the Mansfield Park recreation hall on Monday, Aug. 26, when more than 50 people spoke on the record registering their concerns for the permit, which is being considered by the state.

Torn, with his wife Susan and son Chris Torn, who will be the director of the planned youth camp, told the crowded room he did not intend to dump effluent into their pristine waters, despite applying for a permit that would allow him to discharge 49,000 gallons of treated wastewater per day into the 3.5 mile spring-fed creek.

“We aren’t proposing that,” Torn said. “It’s that simple.”

After showing a slideshow of children enjoying outdoor activities, which many viewed as a shameful attempt at emotional blackmail, Torn took the podium. He provided a litany of benefits the residential youth summer camp would bring to the community, including the creation of 10 to 15 jobs, the issuance of 20 to 30 scholarships for kids ages 7 to 17, the installation of eight miles of high fiber internet in an otherwise remote area, an $18 million construction budget that is mostly being spent locally and an $80 million economic impact over the next 10 years.

Further, he promised the crowd that he would never discharge effluent into the creek. He said he worked with TCEQ to draft into his permit request the requirement that he recycle at least 75 percent of treated wastewater.

“What we’ve been working on for 18 months is a way that we can be a good partner in this community for a long time,” Torn said.

Torn owns and operates the Montgomery County, Arkansas-based Camp Ozark, which serves youth campers every summer. There, he said he runs a zero-discharge wastewater system. In Texas, he would have to apply for a Texas Land Application Permit (T-LAP) to run zero-discharge. But the requirements to comply, he said, don’t fit in with his master plan.

“I looked at that. I looked at it hard,” Torn said, regarding a T-LAP permit. “I discarded because the requirements of TCEQ are much stricter than in Arkansas.”

Torn said the zero discharge permit would require him to dig a four- to eight-acre retention lake on the 700-acre property.

“Because of the master plan of our property, this lake would be located right next to our neighbor, Mr. Blackwell,” Torn said, speaking of Charles and John Blackwell, who own property next door.

Claiming he found a solution and compromise, Torn said he applied for a 210 Reuse permit, which allows the owner to reuse effluent on a voluntary basis. However, he said he had written into the permit that he be required to reuse 75 percent.

“We don’t have to build a lake that doesn’t look good to Mr. Blackwell, plus we will treat on a much, much higher standard,” Torn said. “There is no lake under a 210 Reuse permit. Or we can build a smaller lake. I control that because I have the right to discharge even though I’m not using it.”

The other 25 percent, he said, would generate 1.5 gallons per minute in the summer, which he also promised to reuse.

“We’re never going to discharge,” Torn said. “It makes absolutely zero sense for me to stand up here tonight to tell you I’m never going to discharge and then turn around and discharge. We’re going to be here for the next 50 to 100 years. If I stand up here and tell you one thing and do the opposite., that would be so stupid on my part.”

Stating his promises and alleged good intentions weren’t enough, the downstream property owners and other concerned citizens said any permit that allows the discharge of effluent into the creek should be denied. Fearing it precedent-setting, they said this could be the first of innumerable similar developments in the area.

Several questions, requests and suggestions were registered by Torn’s youth camp neighbors, including changing the discharge point so that the effluent would flow across his property before it reached any adjacent properties. When Torn said that was not an option, Beyrl Armstrong said donors would be willing to pay for the redesign.

“We worked with TCEQ. From their standpoint, they’re perfectly fine with us discharging,” Torn said. “We’ve come up with what know is a win win win situation.”

Zachary Lyman asked Torn if he was willing to change the discharge reuse requirement from 75 percent to 99 percent, thereby eliminating the mandate that he build a retention pond.

“The reason we are here is frankly because we’re terrified. We don’t want you to have the ability to dump into our rivers and our creeks,” Lyman said. “For the comfort of our community so that we might be able to trust you more, would you be willing to change the discharge. You would be binding yourself so that we would feel more comfortable.”

Torn said no.

Several people expressed their concerns that the effluent runoff would perpetuate algae bloom and irreparably damage the stream forever, which families have enjoyed and lived on for generations.

“My grandfather bought our property in 1922 because of the water. I grew up on Hondo Creek. My children grew up on Hondo Creek,” Glen Stern said, holding up his grandson - the fifth generation in his family on the creek. “If this water is so good, why don’t you put it on your own property. Put your campers in the treated water.”

Fiona and Ronny Nolan said they have lived on the Hondo Creek for close to 50 years. They said their only source of drinking water comes from the creek.

“If you do this, can we still drink the water?” Fiona Nolan asked.

James Griffin, who lives on Commissioners Creek, said his property is 1.5 miles from the discharge point.

“We built our house 30 yards right above the creek. Although we’ve had very low flow with droughts, we have had very clear water.” Griffin said, adding the water Torn has impounded has already disrupted their water quality. “In essence, our creek flow will be determined by how much he chooses to release.”

Margaret Skinner said the water flow during drought is not great enough to wash what effluent or chemicals are put into the creek.

“Millions of lives depend on the creek for good health,” Skinner said. “The animals, birds and fish. Humans will stay away from the stench of the creek beds, but animals will be forced to drink or die.”

Margo Denke Griffin said parts of the creek are already stagnated with algae where it once ran clear.

“This beauty has suffered since their creation of a recreational lake upstream,” Denke Griffin said. “The person who has applied for this permit has drained it. Our creek has insufficient flow to heal from any discharge.”

If it is granted, Torn’s TCEQ permit will be the only one among 80 others that allows discharge into the creek.

“No one has ever received a permit like that in the Upper Nueces basin,” Denke Griffin said. “We welcome you, but we do not welcome your discharge.”

Representatives for Senator Dawn Buckingham and State Representative Andrew Murr were present, as well as several Bandera County elected officials. TCEQ representative Brad Patterson said all comments made on the record and submitted in writing would be considered and TCEQ would establish a formal response, including whether any changes to the permit request were made as a result of the comments.

Concluding the comment period, John Blackwell said he and his brother Charles - whom Torn referenced as the reason he did not want to apply for a zero discharge permit - would approve a storage tank near their property line.

To follow the permit, go to www.tceq.texas.gov and enter permit number WQ0015713001 in the search bar. For more information on Friends of the Hondo Canyon, which has been formed to educate the public and battle the permit, go to www.friendsofhondocanyon.org.

Torn, with his wife Susan and son Chris Torn, who will be the director of the planned youth camp, told the crowded room he did not intend to dump effluent into their pristine waters, despite applying for a permit that would allow him to discharge 49,000 gallons of treated wastewater per day into the 3.5 mile spring-fed creek.

“We aren’t proposing that,” Torn said. “It’s that simple.”

After showing a slideshow of children enjoying outdoor activities, which many viewed as a shameful attempt at emotional blackmail, Torn took the podium. He provided a litany of benefits the residential youth summer camp would bring to the community, including the creation of 10 to 15 jobs, the issuance of 20 to 30 scholarships for kids ages 7 to 17, the installation of eight miles of high fiber internet in an otherwise remote area, an $18 million construction budget that is mostly being spent locally and an $80 million economic impact over the next 10 years.

Further, he promised the crowd that he would never discharge effluent into the creek. He said he worked with TCEQ to draft into his permit request the requirement that he recycle at least 75 percent of treated wastewater.

“What we’ve been working on for 18 months is a way that we can be a good partner in this community for a long time,” Torn said.

Torn owns and operates the Montgomery County, Arkansas-based Camp Ozark, which serves youth campers every summer. There, he said he runs a zero-discharge wastewater system. In Texas, he would have to apply for a Texas Land Application Permit (T-LAP) to run zero-discharge. But the requirements to comply, he said, don’t fit in with his master plan.

“I looked at that. I looked at it hard,” Torn said, regarding a T-LAP permit. “I discarded because the requirements of TCEQ are much stricter than in Arkansas.”

Torn said the zero discharge permit would require him to dig a four- to eight-acre retention lake on the 700-acre property.

“Because of the master plan of our property, this lake would be located right next to our neighbor, Mr. Blackwell,” Torn said, speaking of Charles and John Blackwell, who own property next door.

Claiming he found a solution and compromise, Torn said he applied for a 210 Reuse permit, which allows the owner to reuse effluent on a voluntary basis. However, he said he had written into the permit that he be required to reuse 75 percent.

“We don’t have to build a lake that doesn’t look good to Mr. Blackwell, plus we will treat on a much, much higher standard,” Torn said. “There is no lake under a 210 Reuse permit. Or we can build a smaller lake. I control that because I have the right to discharge even though I’m not using it.”

The other 25 percent, he said, would generate 1.5 gallons per minute in the summer, which he also promised to reuse.

“We’re never going to discharge,” Torn said. “It makes absolutely zero sense for me to stand up here tonight to tell you I’m never going to discharge and then turn around and discharge. We’re going to be here for the next 50 to 100 years. If I stand up here and tell you one thing and do the opposite., that would be so stupid on my part.”

Stating his promises and alleged good intentions weren’t enough, the downstream property owners and other concerned citizens said any permit that allows the discharge of effluent into the creek should be denied. Fearing it precedent-setting, they said this could be the first of innumerable similar developments in the area.

Several questions, requests and suggestions were registered by Torn’s youth camp neighbors, including changing the discharge point so that the effluent would flow across his property before it reached any adjacent properties. When Torn said that was not an option, Beyrl Armstrong said donors would be willing to pay for the redesign.

“We worked with TCEQ. From their standpoint, they’re perfectly fine with us discharging,” Torn said. “We’ve come up with what know is a win win win situation.”

Zachary Lyman asked Torn if he was willing to change the discharge reuse requirement from 75 percent to 99 percent, thereby eliminating the mandate that he build a retention pond.

“The reason we are here is frankly because we’re terrified. We don’t want you to have the ability to dump into our rivers and our creeks,” Lyman said. “For the comfort of our community so that we might be able to trust you more, would you be willing to change the discharge. You would be binding yourself so that we would feel more comfortable.”

Torn said no.

Several people expressed their concerns that the effluent runoff would perpetuate algae bloom and irreparably damage the stream forever, which families have enjoyed and lived on for generations.

“My grandfather bought our property in 1922 because of the water. I grew up on Hondo Creek. My children grew up on Hondo Creek,” Glen Stern said, holding up his grandson - the fifth generation in his family on the creek. “If this water is so good, why don’t you put it on your own property. Put your campers in the treated water.”

Fiona and Ronny Nolan said they have lived on the Hondo Creek for close to 50 years. They said their only source of drinking water comes from the creek.

“If you do this, can we still drink the water?” Fiona Nolan asked.

James Griffin, who lives on Commissioners Creek, said his property is 1.5 miles from the discharge point.

“We built our house 30 yards right above the creek. Although we’ve had very low flow with droughts, we have had very clear water.” Griffin said, adding the water Torn has impounded has already disrupted their water quality. “In essence, our creek flow will be determined by how much he chooses to release.”

Margaret Skinner said the water flow during drought is not great enough to wash what effluent or chemicals are put into the creek.

“Millions of lives depend on the creek for good health,” Skinner said. “The animals, birds and fish. Humans will stay away from the stench of the creek beds, but animals will be forced to drink or die.”

Margo Denke Griffin said parts of the creek are already stagnated with algae where it once ran clear.

“This beauty has suffered since their creation of a recreational lake upstream,” Denke Griffin said. “The person who has applied for this permit has drained it. Our creek has insufficient flow to heal from any discharge.”

If it is granted, Torn’s TCEQ permit will be the only one among 80 others that allows discharge into the creek.

“No one has ever received a permit like that in the Upper Nueces basin,” Denke Griffin said. “We welcome you, but we do not welcome your discharge.”

Representatives for Senator Dawn Buckingham and State Representative Andrew Murr were present, as well as several Bandera County elected officials. TCEQ representative Brad Patterson said all comments made on the record and submitted in writing would be considered and TCEQ would establish a formal response, including whether any changes to the permit request were made as a result of the comments.

Concluding the comment period, John Blackwell said he and his brother Charles - whom Torn referenced as the reason he did not want to apply for a zero discharge permit - would approve a storage tank near their property line.

To follow the permit, go to www.tceq.texas.gov and enter permit number WQ0015713001 in the search bar. For more information on Friends of the Hondo Canyon, which has been formed to educate the public and battle the permit, go to www.friendsofhondocanyon.org.