September 19, 2020

Frontier Tales

By Rebecca Huffstutler Norton

The Bandera Prophet

There is nothing like the feeling of receiving a handwritten letter or card in the mail to brighten one’s day. Today’s text messages and emails lack the tactile sensation of eagerly opening an envelope and seeing the handwriting of a loved one. On the Texas frontier, letters were the only way to receive news of distant loved ones. Yet, getting the letters from one remote place to another had its challenges.

Often times, general stores and even private homes would serve as a make-shift post office. In Pipe Creek, the home of A.M. Beekman served as the post office, while Mr. Beekman was the first postmaster. The post office for the Tejano settlement of Polly was located inside the store of Francisco Gerodetti, an Italian immigrant. Not only could Gerodetti’s customers pick up their mail, but they could purchase groceries, needed supplies, and his home-made wine.

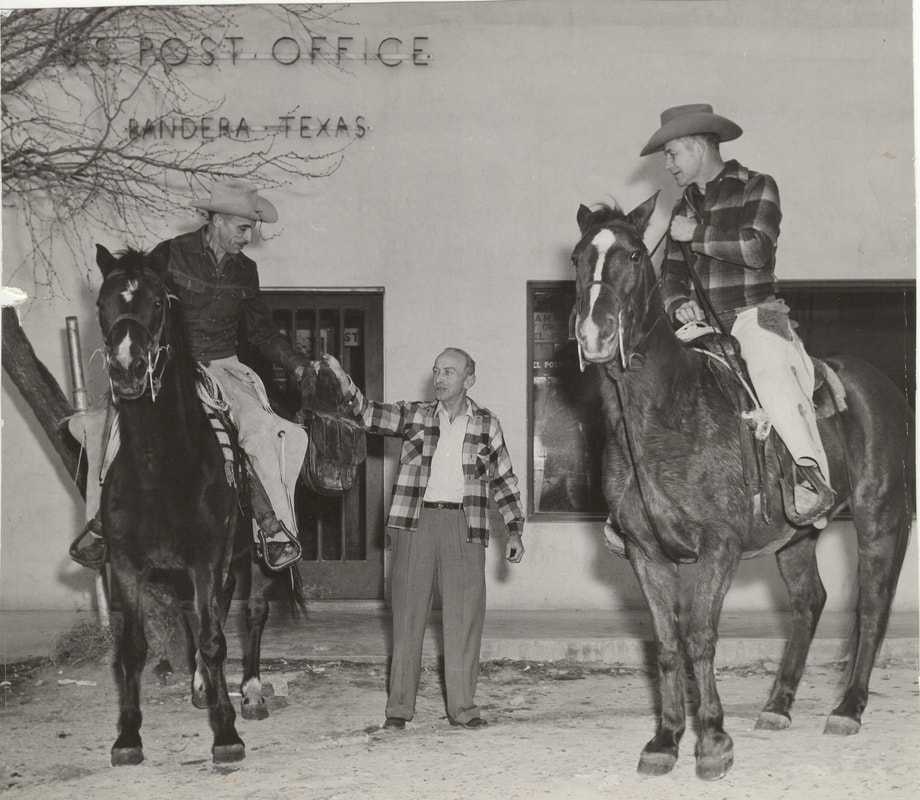

Early delivery of the mail to Bandera was irregular as it was brought by horseback from Castroville when travel over rough terrain was not only difficult, but dangerous. Christian Santleben and his son, August, were contracted to bring the mail to settlers living in Bandera County. Fourteen-year-old, August, carried a six-shooter for protection since skirmishes with the area’s Native Americans were common. He later recalled he made the 64-mile round trip between Bandera and Castroville at least 100 times. Writing of his adventures to J. Marvin Hunter for Hunter’s One Hundred Years in Bandera, August told of one frightening encounter. On one trip to Castroville, a young boy wishing to visit his family in Castroville hitched a ride on the back of August’s horse. When August took a wrong turn, he came upon a group of men which he presumed to be hostile Indians. He quickly turned his horse around to escape but his companion panicked and jumped off, running into the brush. August found his way to the Mitchell Ranch where a group of Mexican men later arrived with his companion. They had seen his frightened haste in running away from them and they wanted to assure everyone that it was just their group picking pecans and not Indians.

During the Civil War, the Confederate government tried to maintain postal deliveries but failed miserably. Sometimes the mail would not be delivered in Bandera for weeks at a time. Early settler, Amasa Clark, recalled in his memoirs that he would read the Galveston newspaper a little bit at a time to make the newspaper last until the next mail delivery. By 1880, four mail lines were operating to Bandera from San Antonio, Castroville, Rio Medina, and Center Point.

Postal services were so improved by 1883 that Postmaster T. A. Peacock boasted in the Bandera Enterprise that mail delivery from San Antonio was daily, except for Sunday, mail to Medina City was Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays and mail to and from Waresville was twice a week. A few years later, the San Antonio mail line was discontinued and replaced with a small passenger and mail line which was established between Bandera and Boerne.

Many small settlements throughout the Hill Country had their own post offices which often became the center of the community. Later when these small towns began to become more integrated into larger settlements, many of the post offices were closed and the towns ceased to exist. Lima, Texas was one such town. After their post office closed in 1924, the small town slowly died. By the 1940s, Lima was no longer labeled on county highway maps. A testament to how essential the presence of a post office could be for the livelihood of a community and how integrated our civic life is to a vibrant, functioning postal service.

Often times, general stores and even private homes would serve as a make-shift post office. In Pipe Creek, the home of A.M. Beekman served as the post office, while Mr. Beekman was the first postmaster. The post office for the Tejano settlement of Polly was located inside the store of Francisco Gerodetti, an Italian immigrant. Not only could Gerodetti’s customers pick up their mail, but they could purchase groceries, needed supplies, and his home-made wine.

Early delivery of the mail to Bandera was irregular as it was brought by horseback from Castroville when travel over rough terrain was not only difficult, but dangerous. Christian Santleben and his son, August, were contracted to bring the mail to settlers living in Bandera County. Fourteen-year-old, August, carried a six-shooter for protection since skirmishes with the area’s Native Americans were common. He later recalled he made the 64-mile round trip between Bandera and Castroville at least 100 times. Writing of his adventures to J. Marvin Hunter for Hunter’s One Hundred Years in Bandera, August told of one frightening encounter. On one trip to Castroville, a young boy wishing to visit his family in Castroville hitched a ride on the back of August’s horse. When August took a wrong turn, he came upon a group of men which he presumed to be hostile Indians. He quickly turned his horse around to escape but his companion panicked and jumped off, running into the brush. August found his way to the Mitchell Ranch where a group of Mexican men later arrived with his companion. They had seen his frightened haste in running away from them and they wanted to assure everyone that it was just their group picking pecans and not Indians.

During the Civil War, the Confederate government tried to maintain postal deliveries but failed miserably. Sometimes the mail would not be delivered in Bandera for weeks at a time. Early settler, Amasa Clark, recalled in his memoirs that he would read the Galveston newspaper a little bit at a time to make the newspaper last until the next mail delivery. By 1880, four mail lines were operating to Bandera from San Antonio, Castroville, Rio Medina, and Center Point.

Postal services were so improved by 1883 that Postmaster T. A. Peacock boasted in the Bandera Enterprise that mail delivery from San Antonio was daily, except for Sunday, mail to Medina City was Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays and mail to and from Waresville was twice a week. A few years later, the San Antonio mail line was discontinued and replaced with a small passenger and mail line which was established between Bandera and Boerne.

Many small settlements throughout the Hill Country had their own post offices which often became the center of the community. Later when these small towns began to become more integrated into larger settlements, many of the post offices were closed and the towns ceased to exist. Lima, Texas was one such town. After their post office closed in 1924, the small town slowly died. By the 1940s, Lima was no longer labeled on county highway maps. A testament to how essential the presence of a post office could be for the livelihood of a community and how integrated our civic life is to a vibrant, functioning postal service.