Courtesy photos

February 25, 2021

Discovering a Lost History: African-Americans in Bandera County

By Rebecca Huffstutler Norton

The Bandera Prophet

The stories of the early black residents of Bandera County were traditionally overlooked by local historians who focused more on Bandera’s European immigrants and white settlers. Much was written on the original Polish families who settled along the Medina River to work the cypress mills and on the Mormon families whose site of their short-lived colony sits beneath the waters of Medina Lake.

There are fleeting references to black residents in J. Marvin Hunter’s 100 Years in Bandera. He writes that in 1866, a negro boy was with Frank Buckelew, helping him search for an ox bell, when they found an Indian under a blanket.

The Indian captured Frank Buckelew but the negro boy was able to escape. We know of this story from Buckelew who would go on to write a story of his capture. Hunter also wrote of Dave, no last name, a freedman, who shot his former owner Joseph Poor sometime after the Civil War. Poor survived and Dave was tried in court in Bandera for attempted murder and was eventually acquitted for lack of sufficient evidence, an amazing outcome for the time period.

In her survey of early schools in Bandera County, Gladys Graves included the two schools for “colored” students. Written in the 1950s, Graves gave the most information on the county’s black history up until that time.

It was not until the 1990s that local historians began to pay more attention to this history. Carolyn Edwards, the chair of the Bandera County Historical Commission, wrote a series of articles for Black History month that appeared in the Bandera Bulletin in 1991. Fellow commission member and local historian Peggy Tobin dedicated an entire issue of the historical commission’s newsletter, The Historian, to the county’s black cemetery located on Old Medina Highway. It was in this issue that Mrs. Tobin made the observation that early county histories referred to blacks only as servants, the consensus being Bandera was not a slave-holding county.

The 1860 United States Census proves this to be untrue, showing five registered slaveholders in the county. Captain Charles Jack, who owned one of county’s first ranching operations, was the largest slaveholder with six slaves. The other slaveholders owned one or two slaves, most likely for help in the home and on smaller farms.

After emancipation, a sizeable black community arose. Bandera County offered many job opportunities in the late 1800s as this became a significant cotton growing area. Because of segregation, black residents tended to settle together in an area called Newtonville, located off of Schmidtke Road.

Bandera County Historical Commission Vice-Chair Ray Carter has done extensive research on the settlement that was named for one of the residents, Isaac Newton. The residents established the county’s first black cemetery in the area and the community was anchored by the Newtonville school which was organized in 1882. By 1889, another “colored” school was established on the west side of town where many black families were buying land from Charles Montague and building new homes.

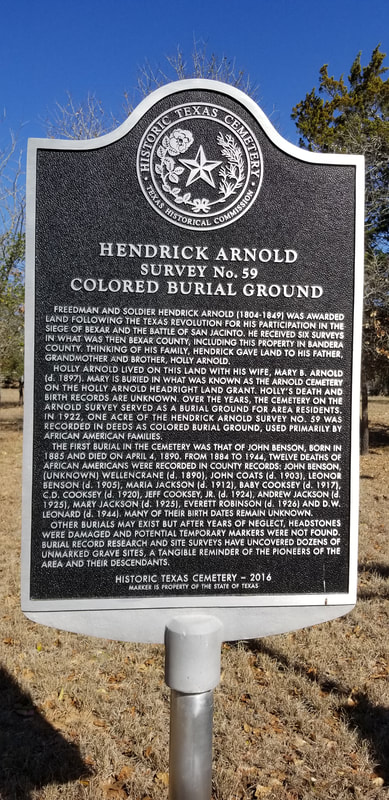

A second black cemetery was officially established when a Deed, dated Oct. 2, 1922, from Mrs. Charles Montague, designated and set aside a one-acre lot as a Colored Burial Ground - “Said above described property to be used for the sole and only purpose of a Colored Burial Ground, a burial ground in which only Negroes are to be buried.” Records show burials were being done on the lot before it was officially established as a cemetery, the first burial being of John Benson who died in 1890.

After World War I, a boll weevil infestation decimated the cotton market. The county’s black population started to decrease. Families left the county to search for work in larger towns and by 1930, only eight residents are listed on the census rolls. The Newtonville school was abandoned as well as the two black cemeteries.

In 1993, the last burial took place in the so-called Colored Cemetery when the family of Bertha Tryon requested permission to bury her there. Mrs. Tryon was a long-time resident of Bandera and, with her husband Buddy, worked for John and Nell Steen at their River Ranch. Buddy Tryon and the family helped clear the property so Mrs. Tryon could be buried there. It was at this time that Carolyn Edwards, as Chair of the historical commission, formally submitted a request to the Commissioners Court to change the name of the cemetery from the Bandera County Colored Cemetery to the Bertha Tryon/ Hendrick Arnold Cemetery.

Arnold was a free black man who settled in San Antonio in 1835. He served as a scout and spy to the Texian army during the Texas Revolution and earned a citation for his bravery in action and service. Arnold never lived in Bandera County though he did hold land grants in this area. He lived on his land grants in south Bexar County along the Medina River and this is where he is buried. The historical commission requested the name change as a way of honoring Arnold’s service to the state and added Bertha Tryon’s name as a way to thank the family for helping with the maintenance of the cemetery.

When Mr. Tryon moved to Kerrville, the cemetery once again fell into disarray. In 1999, with the expressed interest of Commissioner James Mormando, the historical commission renewed their efforts to clean the cemetery and mark the graves. Unfortunately, by this time, the markers that were present in 1991, such as the one for John Benson, had gone missing. Only Bertha Tryon’s gravestone remained.

As part of their early clean-up efforts, the historical commission had the Medina Boy Scouts make headstones for the graves out of wood, but these have disappeared as well. Today, there are small concrete bricks marking the locations of the known graves. There is some confusion of how many graves are actually there and who is buried there. Research by Peggy Tobin found that after 1928, records were no longer maintained that listed race or burial sites.

Perpetual care for the cemetery became a priority for the historical commission. Between 2013 and 2016, under the direction of Chairperson Roy Dugosh, the historical commission once again cleared the cemetery of overgrown vegetation, and commission member Cecil LeStourgeon built limestone pillars at the entrance. In 2016, an iron sign with the name of the cemetery was installed along with a Texas Historical Marker and a dedication service was held to honor those that are known to be buried there. In 2020, Roy Dugosh oversaw the installation of a flag pole.

Plans are underway to make further improvements to the grounds, including possibly encircling the lot with an iron fence and creating a meditation garden. There is a need to complete a ground penetrating radar survey to definitively locate all the graves. To ensure the county’s African American history is not forgotten, the historical commission is hoping to partner with other organizations in Texas to do further research for a Texas Historical Marker to be placed near Newtonville to remember a once thriving black settlement.

There are fleeting references to black residents in J. Marvin Hunter’s 100 Years in Bandera. He writes that in 1866, a negro boy was with Frank Buckelew, helping him search for an ox bell, when they found an Indian under a blanket.

The Indian captured Frank Buckelew but the negro boy was able to escape. We know of this story from Buckelew who would go on to write a story of his capture. Hunter also wrote of Dave, no last name, a freedman, who shot his former owner Joseph Poor sometime after the Civil War. Poor survived and Dave was tried in court in Bandera for attempted murder and was eventually acquitted for lack of sufficient evidence, an amazing outcome for the time period.

In her survey of early schools in Bandera County, Gladys Graves included the two schools for “colored” students. Written in the 1950s, Graves gave the most information on the county’s black history up until that time.

It was not until the 1990s that local historians began to pay more attention to this history. Carolyn Edwards, the chair of the Bandera County Historical Commission, wrote a series of articles for Black History month that appeared in the Bandera Bulletin in 1991. Fellow commission member and local historian Peggy Tobin dedicated an entire issue of the historical commission’s newsletter, The Historian, to the county’s black cemetery located on Old Medina Highway. It was in this issue that Mrs. Tobin made the observation that early county histories referred to blacks only as servants, the consensus being Bandera was not a slave-holding county.

The 1860 United States Census proves this to be untrue, showing five registered slaveholders in the county. Captain Charles Jack, who owned one of county’s first ranching operations, was the largest slaveholder with six slaves. The other slaveholders owned one or two slaves, most likely for help in the home and on smaller farms.

After emancipation, a sizeable black community arose. Bandera County offered many job opportunities in the late 1800s as this became a significant cotton growing area. Because of segregation, black residents tended to settle together in an area called Newtonville, located off of Schmidtke Road.

Bandera County Historical Commission Vice-Chair Ray Carter has done extensive research on the settlement that was named for one of the residents, Isaac Newton. The residents established the county’s first black cemetery in the area and the community was anchored by the Newtonville school which was organized in 1882. By 1889, another “colored” school was established on the west side of town where many black families were buying land from Charles Montague and building new homes.

A second black cemetery was officially established when a Deed, dated Oct. 2, 1922, from Mrs. Charles Montague, designated and set aside a one-acre lot as a Colored Burial Ground - “Said above described property to be used for the sole and only purpose of a Colored Burial Ground, a burial ground in which only Negroes are to be buried.” Records show burials were being done on the lot before it was officially established as a cemetery, the first burial being of John Benson who died in 1890.

After World War I, a boll weevil infestation decimated the cotton market. The county’s black population started to decrease. Families left the county to search for work in larger towns and by 1930, only eight residents are listed on the census rolls. The Newtonville school was abandoned as well as the two black cemeteries.

In 1993, the last burial took place in the so-called Colored Cemetery when the family of Bertha Tryon requested permission to bury her there. Mrs. Tryon was a long-time resident of Bandera and, with her husband Buddy, worked for John and Nell Steen at their River Ranch. Buddy Tryon and the family helped clear the property so Mrs. Tryon could be buried there. It was at this time that Carolyn Edwards, as Chair of the historical commission, formally submitted a request to the Commissioners Court to change the name of the cemetery from the Bandera County Colored Cemetery to the Bertha Tryon/ Hendrick Arnold Cemetery.

Arnold was a free black man who settled in San Antonio in 1835. He served as a scout and spy to the Texian army during the Texas Revolution and earned a citation for his bravery in action and service. Arnold never lived in Bandera County though he did hold land grants in this area. He lived on his land grants in south Bexar County along the Medina River and this is where he is buried. The historical commission requested the name change as a way of honoring Arnold’s service to the state and added Bertha Tryon’s name as a way to thank the family for helping with the maintenance of the cemetery.

When Mr. Tryon moved to Kerrville, the cemetery once again fell into disarray. In 1999, with the expressed interest of Commissioner James Mormando, the historical commission renewed their efforts to clean the cemetery and mark the graves. Unfortunately, by this time, the markers that were present in 1991, such as the one for John Benson, had gone missing. Only Bertha Tryon’s gravestone remained.

As part of their early clean-up efforts, the historical commission had the Medina Boy Scouts make headstones for the graves out of wood, but these have disappeared as well. Today, there are small concrete bricks marking the locations of the known graves. There is some confusion of how many graves are actually there and who is buried there. Research by Peggy Tobin found that after 1928, records were no longer maintained that listed race or burial sites.

Perpetual care for the cemetery became a priority for the historical commission. Between 2013 and 2016, under the direction of Chairperson Roy Dugosh, the historical commission once again cleared the cemetery of overgrown vegetation, and commission member Cecil LeStourgeon built limestone pillars at the entrance. In 2016, an iron sign with the name of the cemetery was installed along with a Texas Historical Marker and a dedication service was held to honor those that are known to be buried there. In 2020, Roy Dugosh oversaw the installation of a flag pole.

Plans are underway to make further improvements to the grounds, including possibly encircling the lot with an iron fence and creating a meditation garden. There is a need to complete a ground penetrating radar survey to definitively locate all the graves. To ensure the county’s African American history is not forgotten, the historical commission is hoping to partner with other organizations in Texas to do further research for a Texas Historical Marker to be placed near Newtonville to remember a once thriving black settlement.