March 2, 2021

Frontier Tales

By Rebecca Huffstutler Norton

The Bandera Prophet

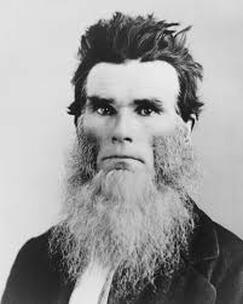

Found in the Frontier Times Museum is a portrait of a man with jet black hair and a wiry gray beard that would be the envy of any member of ZZ Top. Children who visit the museum gaze upon this rather scary looking fellow with horrified fascination. An interesting face like that must have an interesting story to tell.

In the 1840s, Texas fever had spread throughout the southern states and swarms of settlers made their way into the young Republic. Amongst those who made the migration was one Thomas Jefferson Johnson, a dynamic educator and devout Christian. A well-respected teacher who taught in Huntsville, Lockhart, and Webberville in Travis County, he was asked to open a school in Austin, but he was determined to establish an educational institute out in the country.

He traveled throughout Central Texas before deciding on a remote spot in Hays County, in a beautiful valley between two forks of Bear Creek. It was a full day’s journey by wagon from Austin and a day’s journey from any settlement that could offer much needed supplies. But, the waters of Bear Creek ran clear and cold and wood was plentiful.

Johnson built his school out of logs with chimneys made of native rock. In 1852, the Johnson Institute opened its doors. Students came by wagons, traversing over rough hilly roads and crossing rivers before arriving at the Institute. Not deterred by the arduous journey, so many came that the school’s log cabins quickly became overcrowded. Some students even had to make lodging arrangements with nearby farms.

School days began when a bell rang out at 6 a.m. Boys and girls jumped out of bed to dress and bath before eating breakfast and starting their lessons. It was said no one ever saw Professor Johnson comb his hair. He would simply use cold water to run his fingers through his hair, leaving a mop top that resembled the bristles of a brush. Though a strict disciplinarian, the students respected and adored him and, out of affection, christened him “Old Bristletop.”

The students were not above playing tricks on Bristletop, but he was always able to outsmart them. He built a loft to house the more mischievous boys. At night, he would remove the only ladder leading to the loft. He kept the ladder in his room until the morning bell rang out and, only then, would he replace the ladder and yell for the boys to come out. Grateful the professor did not whip them as other teachers would, the boys made a joke out of it and began calling the loft a calaboose.

The success of the school naturally led to improvements. By 1868, the cabins were replaced with a two-story, 10-room, L-shape building built of local limestone. Unfortunately, Johnson died the same year from cholera, which he contracted on a recruiting trip to Galveston. He was buried on the ground where his grave is marked with his last words: "Glory, glory, all is bright ahead."

Next month, we will discover more of how the students were educated at this early Texas school.

In the 1840s, Texas fever had spread throughout the southern states and swarms of settlers made their way into the young Republic. Amongst those who made the migration was one Thomas Jefferson Johnson, a dynamic educator and devout Christian. A well-respected teacher who taught in Huntsville, Lockhart, and Webberville in Travis County, he was asked to open a school in Austin, but he was determined to establish an educational institute out in the country.

He traveled throughout Central Texas before deciding on a remote spot in Hays County, in a beautiful valley between two forks of Bear Creek. It was a full day’s journey by wagon from Austin and a day’s journey from any settlement that could offer much needed supplies. But, the waters of Bear Creek ran clear and cold and wood was plentiful.

Johnson built his school out of logs with chimneys made of native rock. In 1852, the Johnson Institute opened its doors. Students came by wagons, traversing over rough hilly roads and crossing rivers before arriving at the Institute. Not deterred by the arduous journey, so many came that the school’s log cabins quickly became overcrowded. Some students even had to make lodging arrangements with nearby farms.

School days began when a bell rang out at 6 a.m. Boys and girls jumped out of bed to dress and bath before eating breakfast and starting their lessons. It was said no one ever saw Professor Johnson comb his hair. He would simply use cold water to run his fingers through his hair, leaving a mop top that resembled the bristles of a brush. Though a strict disciplinarian, the students respected and adored him and, out of affection, christened him “Old Bristletop.”

The students were not above playing tricks on Bristletop, but he was always able to outsmart them. He built a loft to house the more mischievous boys. At night, he would remove the only ladder leading to the loft. He kept the ladder in his room until the morning bell rang out and, only then, would he replace the ladder and yell for the boys to come out. Grateful the professor did not whip them as other teachers would, the boys made a joke out of it and began calling the loft a calaboose.

The success of the school naturally led to improvements. By 1868, the cabins were replaced with a two-story, 10-room, L-shape building built of local limestone. Unfortunately, Johnson died the same year from cholera, which he contracted on a recruiting trip to Galveston. He was buried on the ground where his grave is marked with his last words: "Glory, glory, all is bright ahead."

Next month, we will discover more of how the students were educated at this early Texas school.