February 6, 2022

Frontier Tales

Black Jack Pershing and the Buffalo Soldiers

By Rebecca Huffstutler Norton

The Bandera Prophet

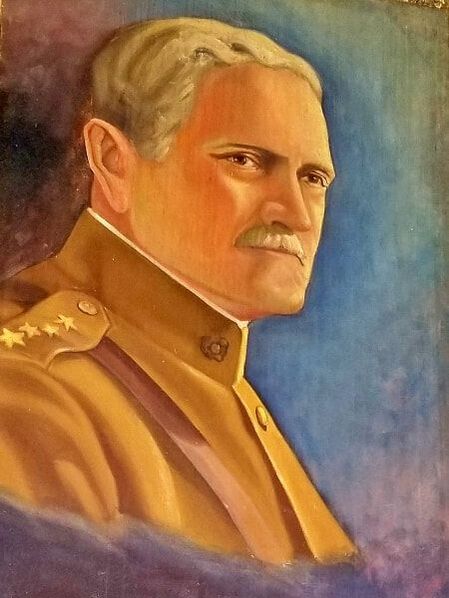

Sitting high on a wall in the Frontier Times Museum is a large portrait of a very distinguished looking military man, General “Black Jack” Pershing. The portrait was not a professional commission, but rather painted by an amateur who was clearly a fan of the famous general. Found in a junk shop in San Antonio, it was one of the first items to be donated to the museum after its opening in May of 1933. Here it has overlooked the comings and goings of all that has happened in the museum for these many decades. At the time it was painted, General Pershing was a national celebrity known for his many military exploits at the turn of the last century when the United States was just beginning to exert its influence on the international stage.

Trained at West Point in the 1880s, John J. Pershing was always proud to call himself a “son of the West.” Known as an excellent horseman, he was well-suited for his tour of duty throughout the west. It is believed he earned his moniker, Black Jack, when he was assigned to the 10th Cavalry, a crack regiment of Black troops that was formed after the Civil War in 1866. The troops were called “Buffalo Soldiers” by the American Plains Indians because their dark, curly hair resembled a buffalo’s coat and because of their aggressive nature of fighting.

When war was declared against Spain in April of 1898, Pershing went with his Buffalo Soldiers to fight in Cuba. While Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders are best remembered for their exploits during the Spanish American War, both Black and White regiments gallantly fought side by side. The battle of San Juan Hill was particularly difficult for the 10th Cavalry as they found themselves fighting as foot soldiers, dismounted from their horses. They suffered numerous causalities. In Pershing’s own words, “Through streams, tall grasses, tropical undergrowth, regardless of causalities, this gallant advance was made.” When the hill was finally taken, Pershing described the carnage, “… the wounded on both sides were cared for alike. One colored trooper stopped at a trench filled with Spanish dead and wounded and gently raised the head of a Spanish lieutenant and gave him the last drop of water in his canteen,” showing honor among men knows no boundaries.

By 1914, Pershing was sent to El Paso to defend the borders of Texas with Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. Mexico was in a state of turmoil as Venustiano Carranza and Pancho Villa struggled for control of the government after the ouster of dictator Porfirio Diaz. The United States favored Carranza which infuriated Villa. Pershing was ordered to organize an expedition into Mexico to defeat Villa. The Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Calvary were among the 6,600 soldiers sent. After fierce fighting, President Wilson, not wanting war with Mexico, called back the troops. It would be the last time the 10th Calvary would perform as a horse cavalry against an enemy. The days of the horse soldiers were coming to an end and Pershing would go on to retire his horse for tanks when he went on to fight in World War One.

Trained at West Point in the 1880s, John J. Pershing was always proud to call himself a “son of the West.” Known as an excellent horseman, he was well-suited for his tour of duty throughout the west. It is believed he earned his moniker, Black Jack, when he was assigned to the 10th Cavalry, a crack regiment of Black troops that was formed after the Civil War in 1866. The troops were called “Buffalo Soldiers” by the American Plains Indians because their dark, curly hair resembled a buffalo’s coat and because of their aggressive nature of fighting.

When war was declared against Spain in April of 1898, Pershing went with his Buffalo Soldiers to fight in Cuba. While Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders are best remembered for their exploits during the Spanish American War, both Black and White regiments gallantly fought side by side. The battle of San Juan Hill was particularly difficult for the 10th Cavalry as they found themselves fighting as foot soldiers, dismounted from their horses. They suffered numerous causalities. In Pershing’s own words, “Through streams, tall grasses, tropical undergrowth, regardless of causalities, this gallant advance was made.” When the hill was finally taken, Pershing described the carnage, “… the wounded on both sides were cared for alike. One colored trooper stopped at a trench filled with Spanish dead and wounded and gently raised the head of a Spanish lieutenant and gave him the last drop of water in his canteen,” showing honor among men knows no boundaries.

By 1914, Pershing was sent to El Paso to defend the borders of Texas with Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. Mexico was in a state of turmoil as Venustiano Carranza and Pancho Villa struggled for control of the government after the ouster of dictator Porfirio Diaz. The United States favored Carranza which infuriated Villa. Pershing was ordered to organize an expedition into Mexico to defeat Villa. The Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Calvary were among the 6,600 soldiers sent. After fierce fighting, President Wilson, not wanting war with Mexico, called back the troops. It would be the last time the 10th Calvary would perform as a horse cavalry against an enemy. The days of the horse soldiers were coming to an end and Pershing would go on to retire his horse for tanks when he went on to fight in World War One.