Photo by Jessica Nohealapa'ahi

June 3, 2022

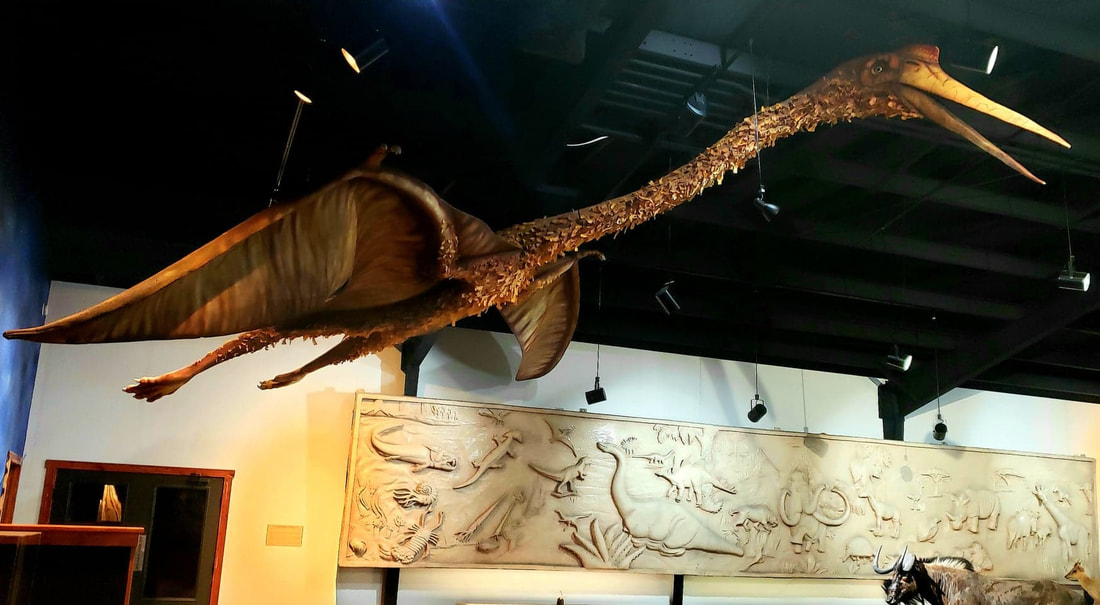

It’s a bird, it’s a plane, it’s a Quetzalcoatlus

Life-size replica on display at the Bandera Natural History Museum

By Jessica Nohealapa’ahi

The Bandera Prophet

Taller than a giraffe, wider than a city bus, and able to soar over tall buildings in a single bound, the Quetzalcoatlus (pronounced Ket-sol-coh-aht-lus) ruled the skies about 80 million years ago.

The Quetzalcoatlus flew overhead during the Cretaceous Period of the Mesozoic Era, and is the namesake of the Mesoamerican mystical serpent god Quetzalcóatl. No shrinking violet, the Aztecs believed Quetzalcóatl to be the god of wind and rain, and the creator of humanity. The largest of all flying reptiles, the Quetzalcoatlus - not to be confused with its popular cousin the pterodactyl, will soon live up to its name in the 21st Century, soaring across the big screen in the upcoming film, Jurassic World: Dominion - set to release this month.

Two hundred and fifty-two years ago, prehistoric Texas was swampland, extending up the North American continent to Canada. Fossils of 21 different dinosaurs and footprints from the Mesozoic have been found across the Lone Star state, including the Quetzalcoatlus, whose first fossil remains were found at Big Bend National Park in 1971. The behemoth was named Quetzalcoatlus Northropi (in tribute to aeronautical engineer Jack Northrop) by Douglas Lawson, the UT Austin graduate student who discovered the fossils. In 2021, the pterosaur was given a new species name: Quetzalcoatlus Lawsoni.

The fossil remnants had a partial wing, with an estimated span of 33 feet. About 25 miles away, Lawson discovered a second site with three skeletal remains in 1972, which he publicly announced three years later. Because all of the fossil finds have been fragmented, the reconstruction of the Quetzalcoatlus is, in part, based on the frames of its close relatives. Certain features, such as a long, toothless beak, and a maximum wingspan up to 52 feet (wider than the Hollywood sign), are widely accepted as accurate.

Many theories have been published regarding how the Quetzalcoatlus lived and ate. The earliest opinions evolved from a fresh-water fish-eating lifestyle, to scavenging carcasses, to skimming the ocean surface, to terrestrial stalking - like a stork.

It may have walked on all fours, and may have been a powerful flier - using its hind legs to push as high as eight feet when taking off. Its fossil remains were found in layers of rock around the same age as the K-T boundary, an indicator that the Quetzalcoatlus disappeared during the mass extinction event that wiped out three quarters of existing life, ending the Cretaceous Period and launching a new era.

Side note: Last month, a new species of a flying reptile was made public. Discovered in Argentina’s Andes Mountains in 2012, the pterosaur has been named the Thanatosdrakon Amaru, “Dragon of Death,” by palaeontologist Leonardo Ortiz. The fossilized remains are the size of a bus with a wingspan, when fully extended, that stretches 30 feet from one tip to the other.

The Quetzalcoatlus flew overhead during the Cretaceous Period of the Mesozoic Era, and is the namesake of the Mesoamerican mystical serpent god Quetzalcóatl. No shrinking violet, the Aztecs believed Quetzalcóatl to be the god of wind and rain, and the creator of humanity. The largest of all flying reptiles, the Quetzalcoatlus - not to be confused with its popular cousin the pterodactyl, will soon live up to its name in the 21st Century, soaring across the big screen in the upcoming film, Jurassic World: Dominion - set to release this month.

Two hundred and fifty-two years ago, prehistoric Texas was swampland, extending up the North American continent to Canada. Fossils of 21 different dinosaurs and footprints from the Mesozoic have been found across the Lone Star state, including the Quetzalcoatlus, whose first fossil remains were found at Big Bend National Park in 1971. The behemoth was named Quetzalcoatlus Northropi (in tribute to aeronautical engineer Jack Northrop) by Douglas Lawson, the UT Austin graduate student who discovered the fossils. In 2021, the pterosaur was given a new species name: Quetzalcoatlus Lawsoni.

The fossil remnants had a partial wing, with an estimated span of 33 feet. About 25 miles away, Lawson discovered a second site with three skeletal remains in 1972, which he publicly announced three years later. Because all of the fossil finds have been fragmented, the reconstruction of the Quetzalcoatlus is, in part, based on the frames of its close relatives. Certain features, such as a long, toothless beak, and a maximum wingspan up to 52 feet (wider than the Hollywood sign), are widely accepted as accurate.

Many theories have been published regarding how the Quetzalcoatlus lived and ate. The earliest opinions evolved from a fresh-water fish-eating lifestyle, to scavenging carcasses, to skimming the ocean surface, to terrestrial stalking - like a stork.

It may have walked on all fours, and may have been a powerful flier - using its hind legs to push as high as eight feet when taking off. Its fossil remains were found in layers of rock around the same age as the K-T boundary, an indicator that the Quetzalcoatlus disappeared during the mass extinction event that wiped out three quarters of existing life, ending the Cretaceous Period and launching a new era.

Side note: Last month, a new species of a flying reptile was made public. Discovered in Argentina’s Andes Mountains in 2012, the pterosaur has been named the Thanatosdrakon Amaru, “Dragon of Death,” by palaeontologist Leonardo Ortiz. The fossilized remains are the size of a bus with a wingspan, when fully extended, that stretches 30 feet from one tip to the other.